This guest post is by Maurice Mierau, an adoptive parent and author.

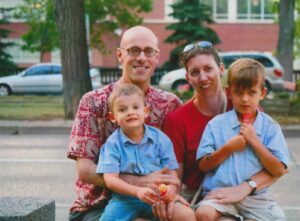

My wife Betsy and I adopted two brothers in Ukraine, Peter and Bohdan, in 2005, when they were five and three years old.

My wife Betsy and I adopted two brothers in Ukraine, Peter and Bohdan, in 2005, when they were five and three years old.

I’m a professional writer, and have just published a book about that experience called Detachment: An Adoption Memoir, but I’ll tell the story here from the perspective of what I wish we’d known in advance.

We adopted in Ukraine because my Mennonite father’s family lived there until World War II, and so I had deep family roots in the country, but also because some neighbours had successfully adopted two children there in the same time period.

Betsy and I were not able to have biological children, so we started investigating adoption in the province of Manitoba, where we live, in 2003.

A social worker did a home study, and we went through adoption education classes, a lot of paperwork, and then worked through an adoption agency active in Ukraine.

In 2003 attachment disorder was just a slide in a presentation during class, and it did not make much impression on me.

I could have defined the term, but the real-world impact of children being chronically neglected or worse during their first three years was not something I understood in a visceral way.

My book begins with me having a breakdown in a psychologist’s office in 2009. That section is called “Shrinking,” because that’s what it felt like: my world was shrinking.

Our older son Peter had recently tried running away from home. He had serious behavioural issues in school, and we had taken him to a psychologist as well, where he was diagnosed with attachment disorder (AD).

He and Bohdan had been abandoned by their birth mother in Ukraine, and then after a month in conditions that are murky to us even now, went into the orphanage system in Ternopil at the ages of one and three.

Then they were placed in orphanages 140 kms apart about a year later. Peter’s AD diagnosis came about one year after he came to Canada. During that year he was a joy, and we thought that everything would be easy.

That was naïve. Peter had gone through a honeymoon period, as many kids do who have AD.

Our youngest, Bohdan, also struggled with understanding his mother’s abandonment, a circumstance that not even grownups can fully comprehend.

My family, my marriage, the things I value most stood at the brink in 2009.

Often in an adoptive family it is the parents who need to change and adapt the most—children have an astonishing, innate ability to adapt, to learn a new language as ours did, to advance their emotional intelligence.

In our family’s case the person who needed to change the most was me.

My book is titled Detachment because of my own struggle, parallel to Peter’s, to attach and engage with my new family. I write about my Mennonite father’s traumatic childhood fleeing from Soviet Ukraine with the German army in 1943, an orphan by the age of ten.

His earliest memory is a Holocaust atrocity, but he barely remembers his mother’s rape; today we’d probably say a child with his background had PTSD.

In order to change as a parent and a husband, and empathize more with my kids’ experience, I needed to empathize more with my father.

Because I’m a writer, I did that through storytelling, through interweaving the story of adopting my sons with my father’s story. Then in the second half of Detachment, I deal with our family life post-adoption.

I support the open adoption concept, and Betsy and I have done all that we can to further investigate our sons’ background and share the information with them as soon as we thought they were mature enough to handle it.

I support the open adoption concept, and Betsy and I have done all that we can to further investigate our sons’ background and share the information with them as soon as we thought they were mature enough to handle it.

Unfortunately open adoption is not really possible in a country like Ukraine that has dysfunctional social systems inherited from the Soviet Union and lacks the resources to fix them.

But we know from experience that children, especially once they hit early adolescence, desperately want to know about their birth families.

People will question (and already have) whether I should have revealed the intimate secrets of our family life in a book and in the media. It’s not a question that I shrug off lightly.

The decision to write and publish the book was anchored in my belief that the issues involved in adoption need more public discussion, and that my struggles, as well as my family’s, are representative in some small way of the struggles other folks have.

In retrospect, I very much wish that we’d known more about attachment disorder, and had access to more community supports (such as respite care) when we had challenges.

The truth is that AD affects children in foster care, in adoptions both domestic and international, and also kids who are refugees of war and violence like my father.

If I were adopting today, I’d do everything possible to learn more about attachment disorder.

Talking to families who have had an adoption experience similar to what you’re contemplating is one of the best things you can do.

Patty Cogen’s book Parenting Your Internationally Adopted Child is excellent for those looking at overseas adoption.

And reading Detachment: An Adoption Memoir will, I hope, give many people more insight into the joys and sorrows, the reality, of what adoption is like.

For me, the experience has been life-changing, gut-wrenching, and profoundly rewarding.

Maurice Mierau is an adoptive father and the author of Detachment: An Adoption Memoir.

Do you have an adoption story? We’d love to share it with your community. Email us any time or find details here.